Speed Management Hub

Speed Management Hub

Overview

The Speed Management Hub is a one-stop-shop for all things related to speed management and road safety.

This tab contains a brief overview of speed management. Other resources available on the hub include:

- Explainer Videos: An animated video series explaining speed management principles and how to implement speed management strategies.

- Tools: A collection of speed management tools to help practitioners evaluate current speeds and analyze changes in crash risk at different speeds.

- Resource Library: A selection of relevant publications—produced by both GRSF and other organizations—related to speed management.

- FAQs: Answers to over 130 frequently asked questions on speed management topics.

Why Focus on Speed?

Speed is one of the main risk factors in road crashes, and is often cited as the leading contributor to fatalities and serious injury on the world’s roads. This is because:

- Higher speed leads to significantly higher crash risk—even small increases in speed can have big consequences.

- The severity of crash outcomes increases rapidly with higher impact speeds.

In September 2020, the UN announced the Decade of Action for Road Safety 2021-2030, targeting at least a 50% drop in road traffic fatalities and serious injuries by 2030. The supporting document, Global Plan for the Decade of Action, outlines strategies that countries can use to achieve this ambitious target. Speed management features prominently in the Global Plan.

As a cross-cutting risk factor, speeding is addressed under various components of the Safe System approach to road safety, such as multimodal transport and land use planning, infrastructure, vehicle design, and road user behavior.

Effective integration of speed management interventions is key to addressing speed. Several interventions are elaborated in our FAQs, including those related to road design and engineering (e.g. 30 kph zones and traffic calming measures); vehicle safety (e.g. Intelligent Speed Assistance); and behavior change (e.g. policy, legislation, and enforcement).

Speed Management News

March 21, 2024

Launch of the Guide for Safe Speeds

February 21, 2024

GRSF and WHO Host Speed Management Manual Webinar

May 03, 2023

New Explainer Video: Traffic Calming Measures

November 09, 2022

New Explainer Video: Speed Management Myths

March 22, 2022

Technology to Help Get Kids to School SafelySpeed Impact Tool

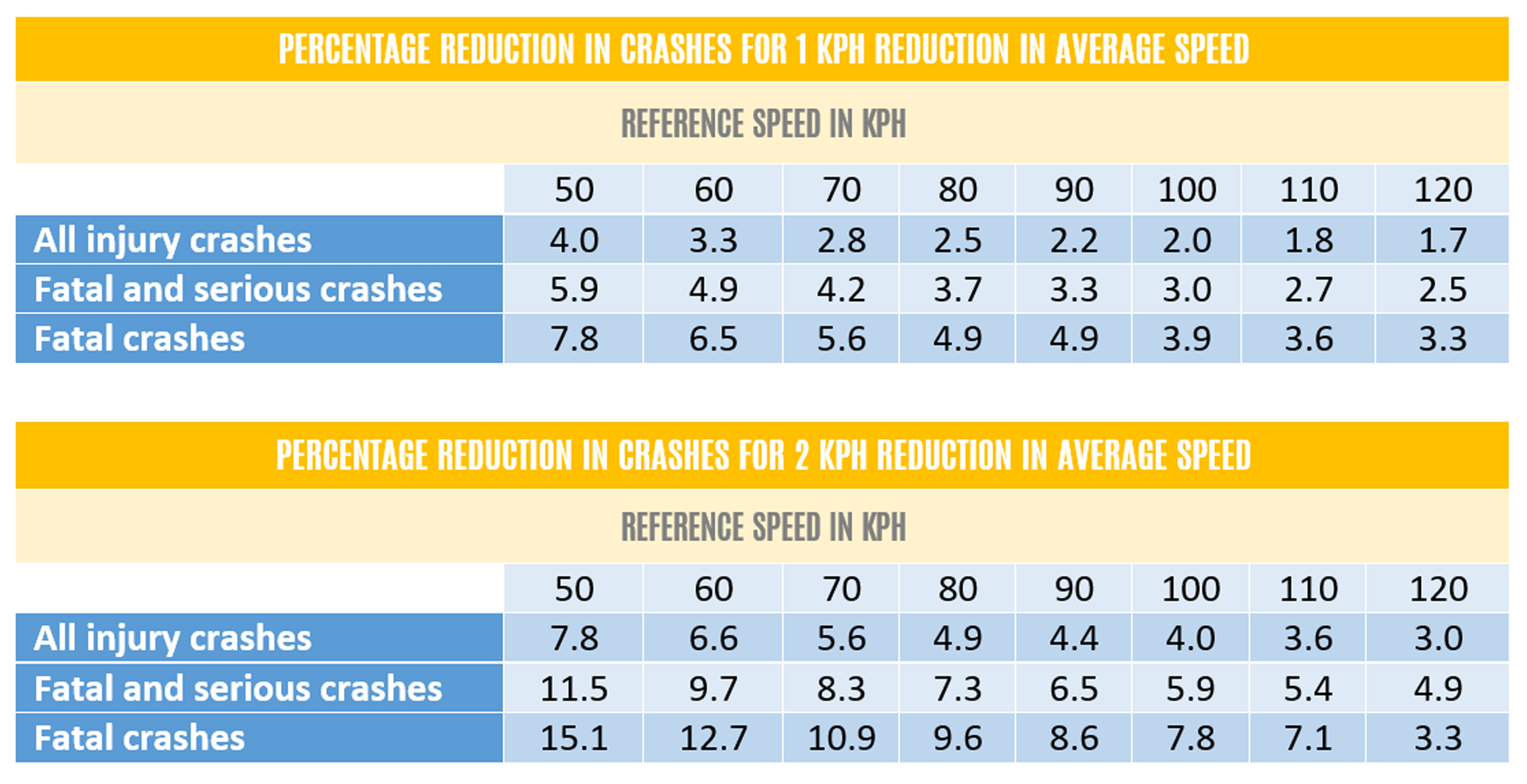

Speed plays a significant role in road safety outcomes. Even small changes in average speeds can have a big impact. Through substantial research, models have been developed that provide guidance on the estimated impact from a change in speed. Early research led to Nilsson’s “Power Model” which identified that a 1% increase in average speed results in approximately a 2% increase in injury crash frequency, a 3% increase in severe crash frequency, and a 4% increase in fatal crash frequency. Reductions in speed lead to equally substantive reductions in deaths and injuries.

More recent research has led to refinements in these models, with the most recent iteration being developed by Rune Elvik and colleagues based on an Exponential Model. This model has now been embedded in a tool that can be downloaded and used by practitioners and decision makers around the world. This basic tool provides estimate on the change in fatal and serious injuries from either an increase or decrease in speed.

Usage instructions are provided within the tool. Like any model, the tool has limitations, including that it has been derived from research in high income countries, and in limited environments. Please read the limitations carefully before using the tool.

Many people do not realize the impact that even small changes can have on safety outcomes, so we hope that this tool will be useful when engaging on discussions around change in speed. Please let us know what you think about this tool.

Speed Survey Tools

Knowing the speed of vehicles at a location is very important for making speed management decisions, including selection of appropriate road safety initiatives. The spot speed is defined as the instantaneous speed of a vehicle at a certain point in time or at a specific location.

Spot speed measurements are used to assess free-flow speeds on a representative sample of vehicles on urban or rural roads. The free-flow speed is a driver’s desired speed on a road at low traffic volume and absence of traffic control devices. In other words, it is the average speed that a motorist would travel if there was no congestion or other adverse conditions (such as bad weather).

Speed collected from a number of different vehicles provides a useful picture regarding road user behavior, and can be used for a variety of purposes. This includes monitoring change in vehicle speeds over time (including against speed targets), intervention selection and evaluations following the implementation of speed-related initiatives.

GRSF has created two speed Excel-based survey tools to help users record and analyze data at spot locations.

- The "speed-based" version of the speed survey tool can be used when a speed measurement device, such as a radar or laser, is available.

- The "time-based" version can be used even when this equipment is not available—in this case, the assessment can be undertaken using a stopwatch to measure the time it take a vehicle to travel between two points.

We hope that it will be useful to practitioners and decision makers, and that it will encourage the greater collection of speed-related data to help in road safety decision making.

-

Speed Management Guide for Safe Speeds: Managing Traffic Speeds to Save Lives and Improve LivabilityMarch 2024

-

Speed Management Speed Management Research: A Summary Comparison of Literature Between High-Income and Low and Middle-Income CountriesFebruary 2024

-

Speed Management Speed Management: A Road Safety Manual for Decision-Makers and Practitioners (2nd ed.)November 2023

-

-

Speed Management Guide for Determining Readiness for Speed Cameras and Other Automated EnforcementJuly 2022

-

Speed Management Road Crash Trauma, Climate Change, Pollution and the Total Costs of Speed: Six Graphs That Tell the StoryJuly 2022

Pagination

Frequently Asked Question

Speed management involves various techniques to reduce/modify the speed of road users, usually motorized vehicles. The purpose is to ensure that speeds are safe for all road users to avoid injuries and death, as well as to improve traffic flow, reduce noise and air pollution, and decrease climate change impacts of road transport.

The management of speed can be achieved through the use of appropriate speed limits, provision of road infrastructure to support these limits, police enforcement, education and community engagement, and vehicle technologies. A mixture of these approaches is often used and the most effective. Speed management should occur as part of a structured, consistent approach that covers the entire road network of interest. However, in many instances, localized changes to speed may be required, often in response to local safety issues.

Under the Safe System approach, safety is the key objective when managing speeds, with a requirement to set and encourage speeds that avoid death and serious injury for all road users, particularly the most vulnerable (including pedestrians and cyclists). Decisions on the appropriate speed often include reference to other societal outcomes besides safety mentioned above, including vehicle journey time, noise and emissions.

Learn more about speed management from this WHO guide and this OECD study.

Question Link:https://www.globalroadsafetyfacility.org/node/1089?ptab=5&pr=17&sr=254

The Safe System approach is a human centric approach in the road transport system which highlights that deaths and serious injuries on our roads are unacceptable and avoidable, and this should dictate the design, use and operation of our road networks. The approach has been adopted by key global organizations (including the World Bank, WHO, United Nations, PIARC, and others) as well as those countries with the best road safety outcomes.

The approach highlights various key principles, including that:

→ People inevitably make mistakes that can lead to road crashes;

→ The human body has a limited physical ability to tolerate crash forces before serious harm occurs;

→ There is a responsibility on those who design, build, and manage roads and vehicles, as well as those who provide post-crash care to prevent crashes resulting in serious injury or death; and

→ All parts of the system must be strengthened to employ their effects so that if one part fails, road users are still protected.

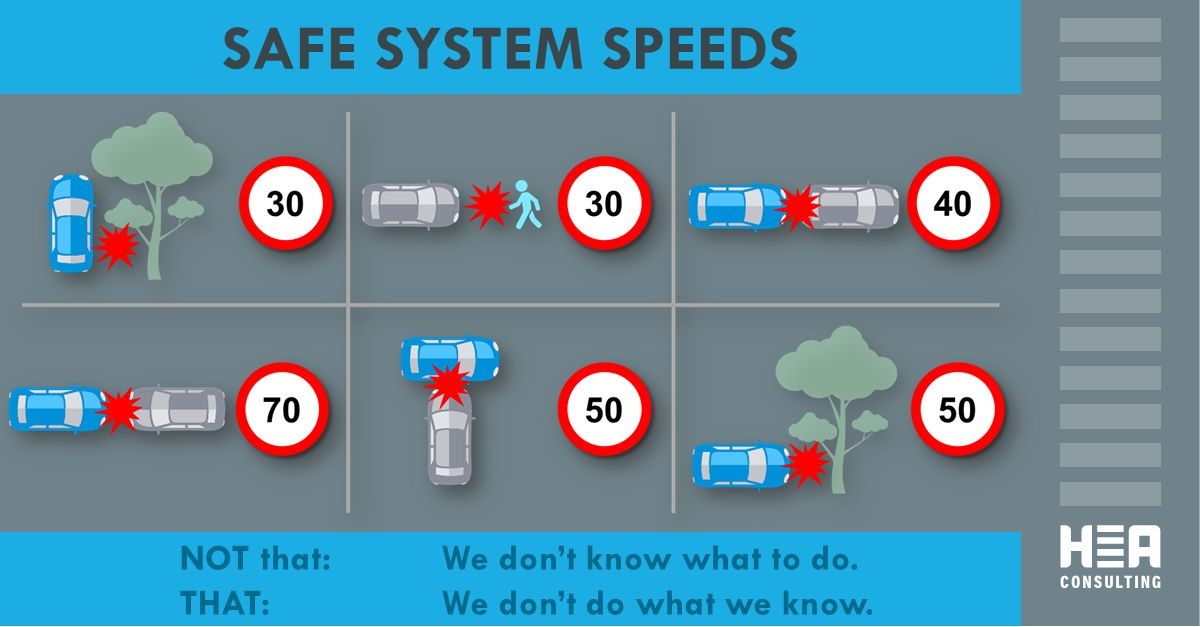

Speed is a critical component within a Safe System. Safe speeds (see Q1.4) are needed to ensure when errors do occur, that they do not result in death or serious injury. The levels which speeds are considered safe depend upon the presence of vulnerable road users, vehicle types (and their protective features), and the protective nature of road and roadside infrastructure. Speeds at or below these levels will help eliminate death and serious injuries, which is the ultimate goal of the Safe System approach.

Learn more from the OECD/ITF Safe System guide here. To understand more about the origins of the Safe System approach, see a summary on Sustainable Safety from the Netherlands here, and on Vision Zero from Sweden here.

Question Link:https://www.globalroadsafetyfacility.org/node/1089?ptab=5&pr=17&sr=253

Speeding refers to road users travelling at speeds which are above the speed limit, also called as excessive speeds (which is dangerous and illegal), and also speeds that are inappropriate for road conditions (e.g. driving too fast during heavy rain or fog). Both of these have negative impacts on road safety outcomes and need to be addressed.

Sometimes a distinction is made between ‘high level’ or excessive speeding (often deliberate, and well above the speed limit) and ‘low level’ speeding (just above the speed limit, and sometimes unintentional). Both have an impact on safety outcomes (see Q8.4 for a discussion on how even small changes in speed can have a big safety impact).

The UN Global Road Safety Performance Targets indicate in target 6 the need that “by 2030, halve the proportion of vehicles travelling over the posted speed limit and achieve a reduction in speed related injuries and fatalities”.

Information on speed limits can be found in Q2.1 and Q2.2, while advice on better management of speeds can be found throughout these FAQs.

Question Link:https://www.globalroadsafetyfacility.org/node/1089?ptab=5&pr=17&sr=669

To be safe and appropriate, speeds need to reflect the type of road users that are likely to be part of the traffic mix, the protection offered by vehicles and road design, and be adapted to conditions, including weather.

When errors do occur (see Q1.2), the outcomes should not result in death or serious injury, and speed plays a critically important role in this. There are only certain forces that the human body can withstand during a crash, so speeds should be managed based on our understanding of this. Pedestrians can typically survive impacts speeds of around 30 kph, above which the chance of survival decreases dramatically. It is likely a similar impact speed applies for other unprotected road users such as motorcyclists and cyclists. At intersections, side impacts at or below 50 kph are survivable. For head-on crashes, road users in modern vehicles with good quality safety features can generally survive an impact at 70 kph with another vehicle of equal mass. To be safe, speeds need to be at or below these critical threshold levels.

If higher speeds are required, then better-quality infrastructure (including separation and crossing facilities for pedestrians; barrier protection systems to prevent head-on crashes etc.; see FAQs in section 3 for further examples) is usually required to support the increase in operating speed and protect road users.

Reaching safe speeds to eliminate death and serious injury should be the ultimate objective for road safety. However, where these speeds cannot be obtained in the short term, less substantial reductions in speed will also produce safety benefits (for information on this see Q1.9 and Q8.4).

Read more about Safe System speed limit setting here.

Question Link:https://www.globalroadsafetyfacility.org/node/1089?ptab=5&pr=17&sr=670

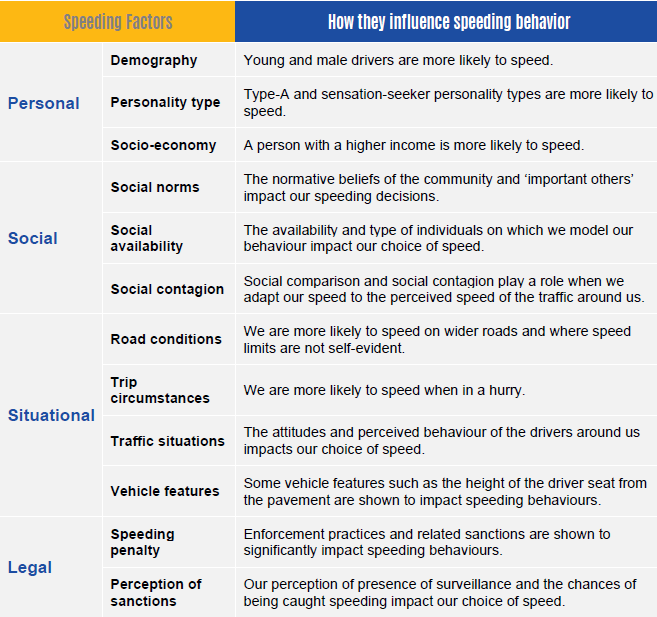

There are several reasons (excuses) why drivers speed and how they rationalize their speeding behavior. This potentially makes speeding behavior change a challenging, complex undertaking. According to robust Research, several factors contribute to speeding. Some of these factors are summarized in the table below:

A recent study characterized motivations and types of speeders using naturalistic driving data (Richard et al., 2012; see also Richard et al., 2013). Speeders were classified into four groups, based on the percentage of trips with speeding and the average amount of speeding per trip, namely:

-

incidental or infrequent speeders, meaning less trips with speeding and little speeding on these trips;

-

situational speeders, meaning less trips with speeding but a lot of speeding on these trips;

-

casual speeders, meaning many trips with speeding but only small amounts of speeding; and

-

habitual speeders, meaning speeding on most trips with a lot of speeding.

A 2020 survey by CarInsurance.com in the US reported that during the current COVID-19 pandemic many countries are reporting more traffic fatalities and handing out more speeding tickets. Fewer drivers on the road are leading motorists to take more risks, including speeding. About one-fifth of those surveyed explained they were late for work, didn’t see the sign, drove as fast as everyone else or had a medical emergency. Other excuses not quite as popular were they were headed for an interview, funeral, date and concert. For further information, see this link.

Additionally, the Transport Accident Commission in Victoria, Australia, in their Road Safety Monitor 2019, reported on drivers’ perceptions of speeds - see here.

Question Link:https://www.globalroadsafetyfacility.org/node/1089?ptab=5&pr=17&sr=827

About 650,000 people are estimated to die annually in road crashes because of speeding (for a definition of speeding see Q1.3), though this is most likely an under-estimate. Various studies indicate that speed is responsible for about 30% to 50% of deaths on the road.

Although many studies indicate this level of contribution, many also qualify this to be an under-estimate, making speed an even higher proportion of road crashes. More significant is that reductions in speed can result in substantially greater levels of fatal and serious injury reduction (60%+).

The relationship between speeds and crash outcome has been captured in various models, most notably Nilsson’s “Power Model”. This shows that a 1% increase in average speed results in approximately a 2% increase in injury crash frequency, a 3% increase in severe crash frequency, and a 4% increase in fatal crash frequency (see Q1.7 to understand better the impact of speed). Thus, this model shows how decreasing speed by only a few km/h can significantly reduce the risks of and severity of crashes. Lower driving speeds also benefit quality of life, especially in urban areas as the reduction of speed mitigates air pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, fuel consumption and noise (see Q1.8 and Q1.9).

Learn more about this topic from WHO here; the European Commission here, ITF here, and the Pan American Health Organization here.

Question Link:https://www.globalroadsafetyfacility.org/node/1089?ptab=5&pr=17&sr=828

The higher the speed, the bigger and the more likely the mess. The operating speed of a vehicle impacts not only crash occurrence, but also the severity of a crash when it happens, through the driver’s field of vision and stopping distance (which covers the time to see and judge the need to stop – judgement time, moving to the brake and pressing it - reaction time, and actually stopping the vehicle - braking time), and also crash kinetic energy and losing vehicle control.

The faster a vehicle is moving, the more information the brain receives. However, the brain can only process a certain amount of information in any given time, which means that at 100 kph, it has to eliminate a large amount of peripheral information. This happens unconsciously. The field of vision therefore decreases as speed increases. See this gif showcasing how a driver’s peripheral vision at higher speeds.

In calculating the stopping distance, judgement and reaction time represent how long a driver takes to see both a hazard and the time it takes the brain to realize the danger and process a reaction to a hazard for example, starting to brake. This means that a vehicle travels further at higher speeds before they can react to a hazard. Although several studies have shown that a driver can react in as little as 1 second, most response times are between 1.5 and 4 seconds. The braking distance is the distance that a vehicle travels while slowing to a complete stop. As your speed increases - so does the distance you travel while your brain is processing information and reacting to it – and so does the distance you need to stop. So, the higher the speed, the higher the braking distance.

The kinetic energy of a moving vehicle is a function of its mass and velocity squared (E=1/2mv2) and this energy must be absorbed in a crash by friction, heat, and the damage suffered by the vehicle as a result of the crash. This means, the more kinetic energy to be absorbed in a crash, the greater the potential for injury to vehicle occupants and anyone hit by the vehicle.

Another way speed impacts road crashes and injury is by losing vehicle control: at higher speeds, cars become more difficult to maneuver - especially on corners or curves or where evasive action is necessary.

At the same time, higher speeds may also add risk for other road users. For example, a pedestrian may have selected a safe location to cross the road with sufficient site-distance to the crest of a hill or corner. However, a speeding driver may cover the distance from the position of not being visible to the crossing pedestrian much faster and thus hit the pedestrian.

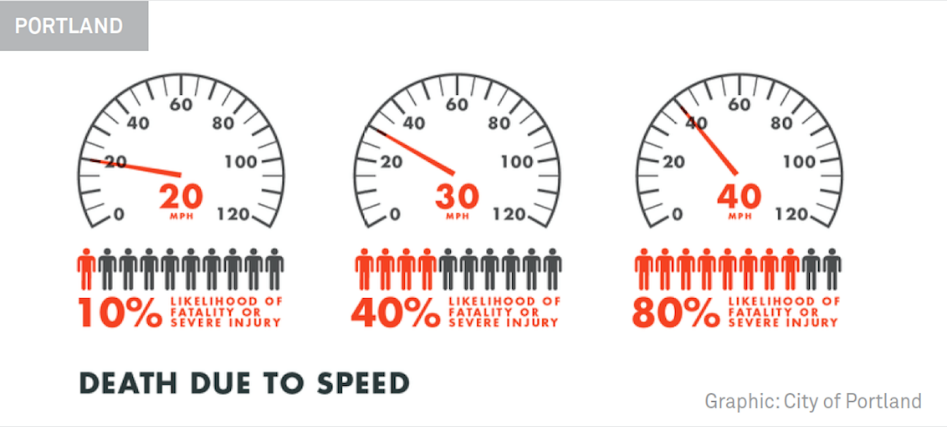

The National Association of City Transport Officials (NACTO) presents the example below for an impactful communication of speed on fatalities from the city of Portland. Access the full document here.

Learn more about the impact of speed from studies in the Americas; Australia and Canada.

Question Link:https://www.globalroadsafetyfacility.org/node/1089?ptab=5&pr=17&sr=829

Speed not only affects road safety but also several environmental and health outcomes, such as:

→ Level of traffic noise: Road noise is the collective sound energy originating from motor vehicles as a result of friction between tire and the road surface, and also from the engine/transmission, aerodynamics, and braking elements. The noise of rolling tires driving on the pavement is found to be the biggest contributor to highway noise which increases with higher vehicle speeds. There is a link between traffic noise and health, with increases in noise leading to negative health outcomes.

→ Air pollution through the level of exhaust emissions: Speed has important impacts on air pollution as it is strongly related to the emissions of greenhouse gases (mainly CO2) and of local pollutants (CO, NOx, HC, particulates). While the process of emission generation is complex and varies within vehicles, across vehicle classifications and engine technologies, oxides of nitrogen (NOx) are produced particularly at high engine operating temperatures (e.g., steady high-speed driving) and a reduction in speed leads to a significant reduction in these emissions. Learn more on speed and environment from OECD (2006).

→ Fuel consumption: Speed also affects fuel consumption with most cars' fuel efficiency reaching a peak at speeds from 60 to 80 kph (equivalent to 35 to 50 miles per hour), but varies for vehicle type. In urban environments with regular slowing and stopping, the most fuel-efficient peak speed may be much lower. Fuel consumption is also linked to air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. In a high-speed environment, i.e., in non-congested conditions, fuel consumption and CO2 emissions increase with increasing speed. However, at lower speed levels, reduced speeds do not necessarily lead to reduced fuel consumption. At speeds below 20 kph, fuel consumption increases significantly as well as air pollution.

→ Overall quality of life for people living or working near the road: As high-speed increases risk of road traffic crashes and injuries, but also air and noise pollution, there is no doubt that speed is linked with poor health and decreased quality of life. Unfortunately, it is a myth that speed means prosperity and progress when in reality, only a marginal benefit can mathematically be derived from increased travel speeds. For example, the extra travel time required for a 10 km journey will be less than 2 minutes if the travel speed is reduced from 50 kph to 45 kph (see Q8.7 and Q8.10 for more details on this myth). In stop/start traffic (which is typical in urban areas due to congestion and intersections) the increase in journey time is likely to be far less.

For more information, check out this study from the OECD (2006).

Question Link:https://www.globalroadsafetyfacility.org/node/1089?ptab=5&pr=17&sr=862

Road safety outcomes are usually measured in terms of the number of crashes and their severity levels, e.g., the total number of crashes; the number of fatalities and serious injuries. Speed plays a central role in all of these road safety outcomes.

Speed is a major contributory factor in over 30% of fatal crashes, as indicated by TRB (1998) and OECD (2006), with some estimates indicating that more than half of the deaths in low and middle income countries due to this cause. Both excess speed (exceeding the posted speed limit) and inappropriate speed (faster than the prevailing road or weather conditions allow) are important crash causation factors. It is also crucial to note that speed affects risk through both likelihood of crash occurrence and crash consequence (for more details see Q1.7).

There have been several research studies to quantify safety outcomes from speed changes. Much of this research comes from comparing outcomes before and after changes are made. This research is best summarized through Nilsson’s “power model” which shows that a 1% increase in average speed results in approximately a 2% increase in injury crash frequency, a 3% increase in severe crash frequency, and a 4% increase in fatal crash frequency. More recent research by Rune Elvik suggests that the relationship between collision risk and speed is exponential, and not a power law. The practical implication of this finding is that the rate of increase in crash risk varies with the initial speed level such that the effect of speed change is higher for high-speed roads than for lower speed roads. Also see here for an update.

Question Link:https://www.globalroadsafetyfacility.org/node/1089?ptab=5&pr=17&sr=912

Unsafe speeds and speeding are more harmful to pedestrians, cyclists, and motorcyclists (aptly called Vulnerable Road Users, or VRUs) than to vehicle occupants. Unsafe speeds are speed limits that are not set in alignment with the Safe System approach – read more about Safe System speed limit setting here and in Q1.4. But why is this the case?

Firstly, the severity of injury depends on the forces to which our bodies are subjected. These in turn depend on the amount by which the speeds at which their bodies are travelling are changed within the very short duration of the impact. The changes in speed are determined by the physical laws of momentum and depend on the speeds at impact and the relative masses of the colliding vehicles, or of the vehicle crashing with a pedestrian or cyclist.

Pedestrians, cyclists, and motorcyclists do not have any or substantial protection against the raw forces of crashes such as crush zones, airbags, and seatbelts. In addition, mass differences are much more extreme in case of a crash between a vehicle and any of these vulnerable road users.

Therefore, a pedestrian, cyclist or motorcyclist is significantly more likely to die or sustain serious injuries at the same impact speed compared to vehicle occupants. For example, the risk of dying or sustaining serious injuries for a pedestrian greatly increases at any impact speed greater than 30 kph; this threshold is 70 kph for a head-on crash between two relatively similar cars. Read more here and in Q1.4.

Secondly, while grossly under-reported, speeding is a major contributing factor to pedestrian and cyclist crashes – read more about this here. It is shown that speeding is also a major contributing factor in motorcycle crashes – over 50% of motorcyclist fatal crashes are reported to be caused by speeding (find more about this here).

Therefore, pedestrians, cyclists and motorcyclists are more likely to suffer from the consequences of unsafe speed and speeding. The International Transport Forum’s report, ‘Speed and crash risk,’ provides more information on this.

It should be noted that even amongst VRUs some groups are more vulnerable such as children, the elderly, and persons with disability to name a few. This is because of potentially more vulnerable physiques, less developed or deteriorating cognitive capacities, and the higher likelihood of relying on walking, cycling or motorcycling as the main mode of transport (See FAQ 2.7).

Question Link:https://www.globalroadsafetyfacility.org/node/1089?ptab=5&pr=17&sr=939

Overwhelmingly, speed is the top contributing factor in road crash fatalities and serious injuries. Speed not only affects the driver, it can also have an impact on the vehicle occupants, pedestrians, cyclists, motorcyclists or other road users. Hence, a sound speed management approach is essential in reducing and preventing road fatalities and injuries.

Thus, the first step in speed management is identifying the speed issue. Note that the issue may be excess speeds (drivers exceeding the posted speed limit) or inappropriate speeds (driving faster than the prevailing road or weather conditions allow) or a speed limit that is too high for safety (see Q1.4 to learn about safe and appropriate speeds). Site reviews including the evaluation of crash data, speed measurements, as well as input from the local traffic police, road authority and communities can be used to confirm if excessive speed is present, to what extent and the reason why. Once the specific issue is identified, specific mitigating measures need to be identified along with the change in speed limit if needed. These measures could be in the form of infrastructure improvement or enforcement.

Learn more on the basics of speed management from WHO and the European Commission.

Question Link:https://www.globalroadsafetyfacility.org/node/1089?ptab=5&pr=17&sr=967

Speed management involves various techniques to reduce/modify the speed of road users, usually motorized vehicles. The purpose is to ensure that speeds are safe for all road users to avoid injuries and death. Other benefits can include improved traffic flow, reduced noise and air pollution, and reduced climate change impacts of road transport.

The management of speed can be achieved through the use of appropriate speed limits, provision of road infrastructure to support these limits, police enforcement, education and community engagement, and vehicle technologies. A mixture of these approaches is often used and considered as the most effective (also see Q1.1).

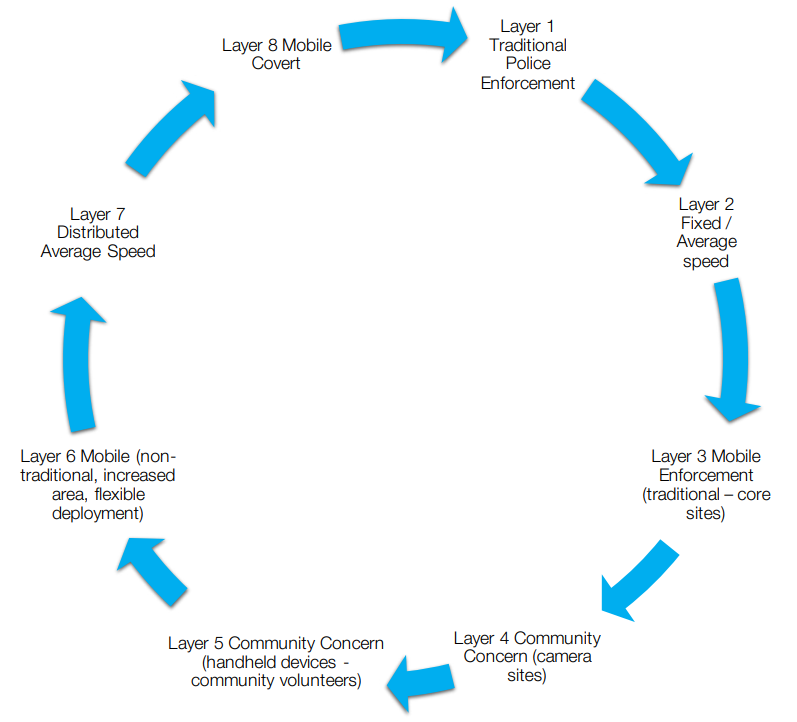

Speed Enforcement is an important and necessary measure for speed management. In many countries speed enforcement has significantly evolved over the past decade with a general increase in the focus of enforcement efforts and the increasingly widespread introduction of automated speed control, which does give a new dimension to the enforcement effort. If undertaken appropriately, speed enforcement can be a very powerful measure (deterrent) that contributes directly to reducing the incidence of speeding and consequently, the frequency and severity of collisions (see Q4.2).

As with all road safety interventions, they should not be implemented in isolation from other key activities. Speed enforcement should be an integrated component of an overall Speed Management Strategy. This is particularly important as speed limits are introduced or changed.

For more information see here.

Question Link:https://www.globalroadsafetyfacility.org/node/1089?ptab=5&pr=17&sr=1001

A speed management strategy (also called a speed management program) is a long-term document that describes an efficient framework for implementing safe speeds for the whole road network in a country. It is based on the Safe System approach and covers the focus areas as well as goals and objectives of speed management. A speed management strategy is usually set at national level in line with the national road safety program, agreed on at high political level and issued by the responsible Department/Ministry.

To succeed, many different organizations, e.g., Ministry of Transport (Road Safety Agency), Ministry of Public Works (Road Authority), Ministry of the Interior (Police), Ministry of Health (Emergency Services), Road Safety Organizations including civil society, are required to be involved in developing the strategy and supporting its implementation.

The speed management action plan defines the concrete actions including timelines to be implemented, e.g., in the fields of engineering, enforcement or public campaigns, with the aim of managing speed and reducing speed related fatalities and serious injury crashes. It is usually issued by the responsible road operator e.g., by a local administration (such as a region, province or city) or a public or private entity (such as a motorway operator/concessionnaire or a large company). The action plan should be based on the national speed management strategy and delineates specific activities to be pursued and steps for their implementation, such as a change in local speed limits for designated roads or the implementation of concrete speed management solutions where speeding is a problem. Furthermore, the action plan includes information for engineers, enforcement agencies and other partner organizations to identify and treat high-risk locations.

Learn more about this topic here and see an Action Plan example here.

Question Link:https://www.globalroadsafetyfacility.org/node/1089?ptab=5&pr=17&sr=1006

A speed management strategy is a coordinated approach based on the Safe System principles to addressing inappropriate speeds and providing a framework for how to create safety and mobility for all road users considering the specific road conditions across a road network (also see Q1.13).

To be successful, a speed management strategy requires a thorough investigation of all the factors affecting speed, such as general driver behavior, road design, land usage, and current legal speed limits, and should cover the following main aspects:

-

Analyzing the current speed management setup and existing challenges;

-

Evaluating the legal and organizational context;

-

Reviewing and improving (where necessary) crash and speed data collection and analysis;

-

Gaining political support for better speed management and enhanced communication on the relationship between speed, speeding, and safety;

-

Seeking the cooperation of national key stakeholders;

-

Defining research needs to increase understanding and knowledge of speeding and resulting crashes;

-

Creating/updating the legal framework for speed management and defining general speed limits that are safe and reasonable;

-

Considering speed-related issues in land use planning;

-

Creating an organizational setup for implementing and improving road design standards for different road and intersection types, that assure safety at the set speed limit;

-

Defining enforcement efforts and appropriate technology that effectively address speeders and deter speeding;

-

Promoting vehicle technologies that reduce speeding, such as Intelligent Speed Adaptation (ISA) (see FAQ6.9 and 6.10);

-

Creating awareness through targeted marketing, communication, and educational messages that focus on high-risk drivers.

For an example of a speed management plan from the US, please see here. For can example from Bogota, Colombia (in Spanish) see here.

Question Link:https://www.globalroadsafetyfacility.org/node/1089?ptab=5&pr=17&sr=1023

Managing speed can not only save high numbers of lives with relatively low investments, but provides an opportunity to improve climate change, health, inclusion, the economy and congestion.

In this context, road design and engineering interventions are often most cost-effective and powerful, especially in cities, towns and villages with low or moderate speed environments. These interventions include road lane narrowing though reducing the width of the travel lanes, raised platform crossings, speed humps, gateway treatments as well as well-designed roundabouts. All are proven to be effective and are typically more sustainable than pure reliance on – often isolated – speed enforcement or education activities. As an example, a recent World Bank study identified that for every $1 invested in traffic calming techniques, benefits of $17 could be expected (see here).

Lowering speed limits at hazardous locations as well as automated speed enforcement (speed cameras) prove to be very cost-effective, especially when combined with road engineering measures. Benefits of more than $14 for every $1 invested could be expected from these measures (see here).

Finally, also vehicle technology provides cost-effective speed management solutions, such as Intelligent Speed Adaptation (ISA) or speed limiters for heavy vehicles, which have proven road safety benefits, as well as positive effects on fuel consumption and emissions. For example, benefits of more than $8 could be expected from every $1 invested in ISA (see here).

If you want to know more about cost-effective speed management solutions, see here.

Question Link:https://www.globalroadsafetyfacility.org/node/1089?ptab=5&pr=17&sr=1035

Powered two-wheelers (PTWs) comprise a significant part of the national vehicle fleet in many low- and middle-income countries (+70% in some) and, globally, the majority of PTW-related deaths (90%) occur in low- and middle-income countries. According to WHO’s Global Status Report on road safety 2018, in South-East Asia, 43% of all road deaths are among riders of motorized two- and three-wheelers, while in the Western Pacific region the figure is 36%. In other regions, the figure is between 9% and 23% of all deaths. Find the WHO report here.

According to “Motorcycle Safety,” a Fact Sheet from the Centre for Accident Research & Road Safety - Queensland (CARRS-Q), fatality and serious injury rates are 30 and 41 times greater, respectively, for motorcyclists than car occupants. There are several factors that contribute to the over-representation of motorcyclists in fatal and serious-injury crashes, namely:

-

Being more exposed to crash forces given their limited physical protection

-

PTWs’ operation mechanism and limited contact with road surface, and their susceptibility to road surface, road, and environmental hazards

-

Instability, braking difficulties and other vehicle safety issues

-

Human factor and road user behaviour issues such as inexperience or lack of recent experience, drivers’ failure to see PTWs and risk taking and aberrant behaviour such as excessive speed.

Specifically, excessive speed is a major factor in motorcyclist crashes. The U.S. Department of Transport’s ‘Traffic Safety Facts – Motorcycles’ points out that 33% of all motorcycle riders involved in fatal crashes in 2017 were speeding, compared to 18 percent for passenger car drivers, 14 percent for light-truck drivers, and 7 percent for large-truck drivers. Find the report here.

Similarly, a recent review of international literature on the impact of speeding on motorcycle safety shows that speeding was reported as a contributing factor in at least a third of all fatal motorcycle crashes – find the review here.

In Thailand, where motorcyclist deaths account for almost three-quarters of all road fatalities, a recent study suggests that speeding motorcyclists are 63% more likely to be involved in casualty crashes compared to those who abide by the speed limit. Find the study here.

A study of motorcycle crashes resulting in hospitalisation in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, shows that at least 26% of motorcyclists were speeding at the time of the crash. Details of the study can be found here.

Question Link:https://www.globalroadsafetyfacility.org/node/1089?ptab=5&pr=17&sr=1036

It is often stated that motorcyclists travel faster than other types of motorized vehicles, and there is good evidence to support this. For example, in 2014, the Belgian Road Safety Institute (BRSI) conducted motorcyclist speed measurement at over 300 locations from around Belgium to: a) obtain a representative and objective measure of the speed driven by motorcyclists in Belgium; and b) compare their speed with that of car drivers and with the actual speed limits.

The main findings of this study confirm that, in general, motorcyclists ride faster and commit more speed infringements than car drivers. Find the survey results here. More specifically:

-

On 30 kph roads, two-thirds of the motorcyclists exceeded the speed limit by more than 10 kph.

-

On 50 kph roads inside built-up areas, the average measured free speed of motorbikes was approximately 3 kph higher than the average free speed of cars, and 5 kph above the speed limit.

-

Outside built-up areas, the average free speed of motorcyclists was significantly higher than that of car drivers: a) 5 kph on 70 kph roads; b) 7 kph on single lane 90 kph roads; c) 4 kph on double lane 90 kph roads

-

On 120 kph highways, the average free speed of motorcyclists was 121 kph.

Furthermore, monitoring motorcyclists’ attitudes towards speeding indicates that many riders believe there should be leeway to allow for travel above the posted speed limit, especially for high-speed roads. The Motorcycle Monitor – the Transport Accident Commission (TAC), Australia – provides an example. Find it here.

A comprehensive study of motorcyclists’ speed behaviour in Malaysia shows that motorcyclists go faster than drivers on primary and collector roads. Specifically, on lower-hierarchy roads, i.e., collector roads, motorcyclists travel almost 20% faster than drivers. Drivers on the other hand travel at higher speeds than motorcyclists on expressways (16%) and secondary roads (10%). Find the report here on the website of the Malaysian Institute of Road Safety Research (MIROS).

Question Link:https://www.globalroadsafetyfacility.org/node/1089?ptab=5&pr=17&sr=1043

Safe transport is a fundamental principle of sustainable mobility. The United Nations defines sustainable mobility as “the provision of services and infrastructure for the mobility of people and goods – advancing economic and social development to benefit todays and future generations – in a manner that is safe, affordable, accessible, efficient, and resilient, while minimizing carbon and other emissions and environmental impact.”

Lowering speeds supports sustainable mobility with a positive impact on road safety as well as environmental and health outcomes, such as air pollution, traffic noise and the overall quality of life by creating livable streets (see Q1.8).

To foster sustainable mobility, the Sustainable Mobility for All (SuM4All) platform was created in 2017. This combines 55 public and private organizations and companies with a common goal to transform the future of mobility. In 2019 SuM4All published the “Global Roadmap of Action – Toward Sustainable Mobility”. This Roadmap consists of six policy papers of which one is dedicated to transport safety and underlines the tremendous importance of speed management for sustainable road transport. It clearly states that in many countries little or no work has been done to give speed management the relevance it needs and that design standards do often not include the many proven cost-effective features that improve safety for all road users (see Q3.2, Q3.3, Q3.4 and Q3.5).

The Roadmap contains a list of policy measures to achieve safety in mobility which has been consolidated and harmonized with the policy measures to achieve all other policy goals toward sustainable mobility. Regarding speed management the following policy goals are especially important:

- Define and enforce speed limits, i.e., define and enforce speed limits according to modal mix, road function, and protective qualities of roads.

- Ensure safe roads design with lower design speeds, i.e., plan and design safe roads and roadsides for lower speeds, including features that calm traffic, and considering the increasing use of bicycles and pedestrian flows in urban areas.

- Set low-noise engineering and traffic management practices, i.e., set traffic management practices to reduce noise pollution, for example, speed limitations, speed humps, traffic lights coordination and roundabouts, and low noise road engineering and maintenance practices, for example low-noise pavement and noise barriers.

- Raise road safety awareness, i.e., ensure sustained communication of road safety as a core business for government and society, emphasize the shared responsibility for the delivery of road safety interventions, and raise awareness about the dangers of speeding.

If you want to know more about sustainable mobility in general and these policy goals in particular, have a look at the Sustainable Mobility for All (SuM4All) publication.

Question Link:https://www.globalroadsafetyfacility.org/node/1089?ptab=5&pr=17&sr=1242

According to the WHO Global Status Report on Road Safety 2018, only 46 countries representing 3 billion people currently have laws setting speed limits that align with best practice. This number has not changed since 2014, and an interactive map with speed limits worldwide can be viewed here.

Globally, there are mainly three different types of speed limits:

1. Default speed limits as specified in relevant legislation (e.g. Road Code), which set the general maximum speed allowed on specific types of roads such as motorways or urban roads; no additional signposting is needed to enforce these limits.

2. Signposted maximum speed limits on roads or sections of roads.

3. Speed limits for specific vehicle or road user types – e.g. farm vehicles, heavy transport vehicles or novice drivers.

It needs to be noted that the default speed limit as well as the posted speed limit indicate the maximum allowable speed for a certain road or stretch of road and not the recommended or appropriate speed at a specific location.

It is also possible to set variable speed limits (VSL). These are flexible restrictions on a certain stretch of road. The speed limit changes according to the current road, traffic, weather or environmental conditions and is displayed on an (electronic) variable message sign (VMS) or on static signs. A VSL may also be used in school zones to provide a safer road environment, to reinforce driver expectations of the likely presence of children and to encourage safe and active travel to school.

Finally, there are also so-called differential speed limits (DSL) with different speed limits for different types of vehicles on the same type of road, e.g. for cars and trucks on motorways.

You want to know more? Click here.

Question Link:https://www.globalroadsafetyfacility.org/node/1089?ptab=5&pr=38&sr=671

Determining the ‘right’, compliant speed limit from a Safe System perspective (see Q1.2) for your road is a very complex task depending on the local factors at hand. Still, you might base your decisions for setting speed limits on the following four principles:

a. Road safety principle

→ Set speed limits to minimize the risk of death or serious injury to all road users where vehicle speeds would result in impact forces exceeding tolerance of the human body.

→ Set speed limits to minimize the risk of death or serious injury to all road users when there is an increased risk of crashes due to a change in operational and/or environmental conditions.

b. Community wellbeing principle

→ Set speed limits, especially on local roads, at a level that supports active transport modes (walking, cycling) and minimizes impacts on amenity.

→ Set speed limits by consulting the affected communities and road users so that expectations, where possible, are considered and impacts of speed changes are understood by the public.

c. Road network efficiency principle

→ Set speed limits in accordance with the functional road class and the standard of the infrastructure.

→ Set speed limits to achieve operating speeds that support an efficient network wide outcome and do not just focus on one isolated section of road.

→ Set speed limits to minimize the overall delay to road users where there is a change in operational conditions (e.g. by variable speed limits, see Q2.1).

d. Road user expectation principle

→ Set speed limits to be consistent with speed limits on roads in a similar environment with similar characteristics and function.

→ Set speed limits so they are clear and easily understood and keep the number of speed limit changes to a minimum.

Among these four, the road safety principle is the most important and should therefore be given priority whenever one principle has to be weighed against another in the decision-making process.

Policy on the minimum length of speed limits is also vital. Speed limits should not change regularly over a few hundred meters, for example. Too many limit changes create confusion and frustration for drivers. Thus, it may be appropriate to set a minimum length for each speed limit. For each section the posted speed limit should be determined as the lowest safe speed for any location within that length.

Learn more about this from Australia here and from Europe here.

Question Link:https://www.globalroadsafetyfacility.org/node/1089?ptab=5&pr=38&sr=672

Spot speed measurements are your way forward. These measurements can be used to assess free flow speeds on a representative sample of urban and rural roads as an important basis for setting up a speed management strategy.

The spot speed is defined as the instantaneous speed of a vehicle at a certain point or a specified location. In road safety work spot speeds are for example used as basic input data for crash analysis, but are also required for road design (e.g., horizontal and vertical curves, super elevation) and to determine the location and size of signs and the design of signals.

There are different techniques to measure spot speeds. The most common devices use either radar (radar meters) or laser sensors (speed lasers), which may be hand-held (so-called ‘speed guns’), mounted in a vehicle or on a tripod. Radar and laser devices require line-of-sight to accurately measure speed and are easily operated by one person. If traffic is heavy or the sampling strategy is complex, two units may be needed.

Besides using radar or laser technology, spot speeds may be estimated manually by measuring the time it takes a vehicle to travel between two defined points on the road, which are a known short distance (e.g., 1 m) apart. This technique is often called stopwatch method. The measurements are very simple and can be conducted by either two observers or by using an enoscope (mirror box) and only one observer. Manual measurements are only applicable for very low traffic volumes and a small sample size taken over a relatively short period of time.

For longer data collection periods pressure contact tubes (pneumatic or electric) can be used. Two contact tubes are placed in the travel lanes of the road and the time is measured between the electric impulse generated when a vehicle runs over the first and then the second tube. The advantages of this method include the ability to collect and store data on 100% of vehicles, and capacity to continuously record for many hours and days. In addition, there is no risk of driver behavior being influenced by seeing a person ahead with a ‘speed gun.’

The most advanced (and expensive) technologies use traffic monitoring cameras and software algorithms to determine speeds from real-time traffic data. An ever-emerging research field is real-time traffic monitoring using mobile phone data or GPS data and estimating traffic speeds using these data sources. Due to the high market penetration of mobile phones not only in HICs but also in LMICs, very detailed spatial data at lower costs than with traditional data collection techniques would be available. Data from cellular phones open new and important developments in transportation engineering but several steps are still needed to achieve a significant confidence in the use of these data, not only in terms of data reliability but also regarding privacy and security issues.

Click here or here to get more details on methods for measuring traffic speeds.

Question Link:https://www.globalroadsafetyfacility.org/node/1089?ptab=5&pr=38&sr=673

Regardless of the speed measurement method used, you might keep in mind that speed survey results highly depend on the way the survey is conducted. Therefore, you might follow these steps:

1. Select appropriate location for the specific purpose of the study considering that the location is safe for the operator and away from specific features that might influence speeds.

2. Select appropriate speed measuring device (e.g., contact tubes) for the specific purpose of the study.

3. Choose sample size considering the different types of vehicles using the roads (motorcycles, cars, lorries), the traffic volume and variables such as time of day, day of week, holidays and weather conditions (e.g., 200 vehicles of each type over a minimum of 2 hours).

4. When measuring free flow speeds select those vehicles that have a substantial headway and are not impeded by other vehicles or other factors (minimum headway of 3-4 seconds is recommended). Note that for some purposes, collection of speeds from all vehicles (i.e., not including a minimum headway) may be desirable.

5. Guarantee minimum influence of the observer and/or equipment on the drivers and their speed (hide observer and recording equipment, if possible).

6. Collect and evaluate the data (minimum evaluation should include average speed and 85th percentile speed).

It is a good idea to repeat speed surveys on a regular basis to show trends in vehicle speeds and monitor impact of speed management on driver behavior. In that case keep in mind the following:

→ Conduct the speed surveys under similar conditions each time, as any variation in collection procedures may result in differences in the speeds recorded.

→ Use the same location as well as the same recording equipment, and preferably the same equipment operator.

You can learn more here from a New Zealand case study, or here from Austroad’s Transport Studies and Analysis Methods. A very useful document for you might also be the Overseas Road Note 11 ‘Urban Road Traffic Surveys’.

Question Link:https://www.globalroadsafetyfacility.org/node/1089?ptab=5&pr=38&sr=674

The free-flow speed is a drivers' desired speed on a road at low traffic volume and absence of traffic control devices. In other words, it is the average speed that a motorist would travel if there was no congestion or other adverse conditions (such as bad weather).

When measuring free flow speeds (see Q2.3) select those vehicles that have a substantial headway and are not impeded by other vehicles or other factors (minimum headway of 3-4 seconds is recommended).

Free flow speeds and 85th percentile speeds are NOT a good guide for selecting speed limits (see Q2.6).

Question Link:https://www.globalroadsafetyfacility.org/node/1089?ptab=5&pr=38&sr=830

The 85th percentile speed is the speed at which 85% of free-flowing vehicles (see Q2.5) are traveling at or below. For example, this speed can be determined by conducting and evaluating a spot speed study (see Q2.3).

The 85th percentile speed is often used by traffic engineers as the basis for road design. In many countries it is still used as primary tool for setting speed limits (Q2.2), and (more controversially) as a reason against lowering or enforcing limits. In this context, the following three misleading arguments for using 85th percentiles for setting speed limits are put forward:

2. The speed dispersion argument, i.e. speed limits near the 85th percentile will minimize the variance of the speed distribution, thereby minimizing opportunities for vehicle conflict and crashes.

3. The enforcement practicality argument, i.e. 85th percentile limits represent a reasonable and realistic benchmark for enforcement.

But none of these arguments are valid. The majority of drivers will not always make well-balanced decisions and select speeds that are safe. Speed choice will often be biased towards personal benefit (e.g. reduction in perceived travel times) as opposed to collective risk (e.g. overall crash risks). Also, drivers’ subjective assessments of risk, and the relationship between speed and risk, are likely to be inaccurate. As far as speed dispersion is concerned many studies showed that the majority of fatal crashes are crashes where speed dispersion is an unlikely factor (e.g. single vehicle crashes, intersection crashes, pedestrian crashes). Finally, nowadays there is strong evidence that setting and enforcing lower speed limits than the 85th percentile speed is feasible, sustainable, and produces safety benefits.

Therefore, countries that have already adopted the safe system approach have discontinued the use of 85th percentiles for speed limit setting. For these countries avoiding death and injury is an absolute priority, and the speed management system as a whole must be based on this philosophy and on an objective assessment of risks.

One short side note: The 85th percentile is an excellent way of demonstrating when speed limits and road design don’t match, and the design of a road is inappropriate for the posted speed limit. Here is an example:

On an inner-urban residential road the speed limit was lowered from 50 kph to 30 kph, without any changes to the road design for the motorized vehicles. The 85th percentile speed of motorized vehicles on this street is measured after the introduction of the lower limit and is found to be still close to 50 kph. This tells you that the road design isn’t doing its job. In the short term you could get the police out with speed guns, but in the long-term the design of the road and its environment should be changed by clever inner-urban road safety engineering solutions (see Question 3.2), which will reduce the 85th percentile speed.

You can learn more here from an ITF report, or here from a guide from Australia.

Question Link:https://www.globalroadsafetyfacility.org/node/1089?ptab=5&pr=38&sr=831

Vulnerable road users such as pedestrians, cyclists or powered two-wheelers have a high risk of severe or fatal injury when they are hit by motor vehicles. This is because they are often physically completely unprotected or only have very limited protection, compared with the safety of a vehicle with a rigid safety shell and airbags.

The probability that a vulnerable road user will be killed if hit by a motor vehicle increases drastically with speed. If hit by a car at 30 kph, 10% of vulnerable road users die, another 15% are seriously injured and 75% are slightly injured. If the impact speed increases to 50 kph these numbers change dramatically: 80% die, 3% are seriously and 17% slightly injured.

The situation is even worse for elderly pedestrians. In fact, pedestrians over the age of 75 are twice as likely to be killed in a crash as those under 34. Elderly people are much more susceptible to injury if they are struck by a vehicle. Their bones are much frailer, and their overall state of health is worse – factors that can make even a minor crash turn lethal. Elderly pedestrians are also more vulnerable to being involved in a crash because of age-related declines in cognitive function and vision.

Children are also highly vulnerable to injuries from motor vehicle impacts. This vulnerability occurs for several reasons including that they have less developed cognitive and perceptual skills and so are less able to make decisions about safe behavior around traffic; the decisions they do make may be less predictable to other road users (such as running after a ball); they are smaller than adults, and so may be harder to see or be seen in traffic; and there is emerging evidence that they are more likely to suffer more severe injuries when struck as pedestrians (especially head injuries).

Under the Safe System approach (see Q1.2) the setting of speed limits considers the risks to road users of sustaining fatal or serious injuries. For example, at locations where there is a significant level of pedestrian or cyclist activity, lower speed limits are appropriate. Similarly, where the potential for conflicts is high (e.g., on busy urban roads with frequent points of access) speed limits are to be set at a level that will minimize the chances of fatal or serious injuries in the event of a crash.

You can learn more on this topic from WHO here, Vision Zero here or Australia here.

Question Link:https://www.globalroadsafetyfacility.org/node/1089?ptab=5&pr=38&sr=863

Motorcyclists are becoming an ever more important component of the transport system. Increasing numbers of people not only in low- and middle-income but also in high-income countries are choosing to ride motorcycles.

This is potentially because of: a) the lower cost of purchasing motorcycles, b) increasing congestions, reduced parking availability, and increasing travel costs, and c) versatility and convenience of riding motorcycles. In some countries (especially high-income countries) there is also a growing interest in riding motorcycles among older and often returning riders, and this can be based on the reasons above, as well as interest in recreational riding.

The International Transport Forum (ITF) points out specific policies and strategies that directly influence a Safe System compliant choice of speed and motorcyclist speeding management policies, namely:

→ Conduct in-depth and naturalistic studies to better understand the role of speed and speeding in motorcyclist fatal and serious injuries.

→ Include motorcyclist safety and mobility in national transport policy including safety, green transport, livability, and sustainability.

→ Develop a policy of modal priority for road users, particularly in urban environments, based on vulnerability and sustainability goals.

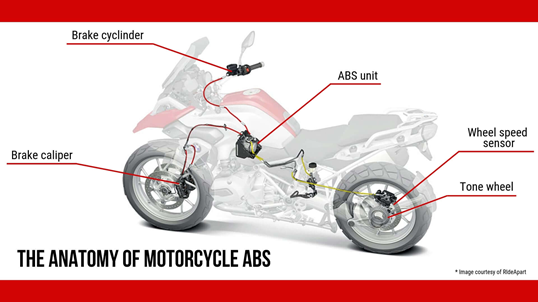

→ Develop mandatory manufacturing rules and regulations to adopt motorcycle safety features such as motorcycle Anti-lock Braking System (ABS), Combined Braking Systems (CBS), stability control, and Automatic Emergency Call Systems. See also question 6.1.

→ Address the current difficulties in enforcing motorcyclist compliance with speed limits, and develop complementary education/enforcement policies and programs to address the motorcyclist excessive speed issue.

→ Develop enhanced enforcement programs with a focus on identified motorcyclist crash risk locations and popular motorcycling routes.

→ Consider zero-tolerance for motorcyclist speed enforcement or a minimal leeway.

Find the ITF reference here.

Question Link:https://www.globalroadsafetyfacility.org/node/1089?ptab=5&pr=38&sr=913

Legal requirements regarding the responsibility for setting of speed limits vary between countries. Regardless of these requirements it is important to involve key stakeholders in the speed limit setting process.

Speed limits should be set based on multiple principles (see Q2.2) to provide safe and efficient travel between destinations. The acceptability of new speed limits will depend on the support from politicians and decision-makers, as well as from the (local) community itself.

Once evidence is produced that speed and speeding are problematic, support from local stakeholders for lowering the speed limit must be obtained and the affected communities and road users should be consulted so that impacts of speed changes are understood by the public and expectations can be managed.

It is also important to involve road engineers, traffic police (noting that these two groups are often legally responsible for instigating speed limit changes), emergency services, and – where necessary – public transport providers as well as communication experts in an early stage to define the most cost-effective and feasible measures in engineering, enforcement and creating support to accompany the new speed limit.

Learn more about this from the WHO speed management manual here. You can also find more about stakeholder and community engagement in Section 4 of Victoria’s Speed Zoning Guidelines.

Question Link:https://www.globalroadsafetyfacility.org/node/1089?ptab=5&pr=38&sr=940

The correct political environment is an essential requirement in road safety, including speed enforcement, if it is to become a government priority for action including funding. Government support for any public policy issue is always subject to constraints including the time and resource constraints necessary for policy development and subsequent legislation.

Political support needs to be expressed in a long-term vision that addresses the greater public good, and to ensure adequate funding is earmarked to implement required initiatives in addition to new legislative and regulatory initiatives. In many cases, speed management is seen to be in direct conflict with other priorities, such as reduced congestion and shorter journey times (which are actually myths – see 8.2 and 8.10), or public spending in other areas. Government priorities can be changed to align better with road safety.

In presenting an enforcement plan to government (at any level) there will be greater success if you include these components:

Present a solid business case – clearly identifying the costs and (significant) benefits (from injury and death reductions); resources required, both human and financial; and, a detailed implementation plan, including a robust monitoring and evaluation component. It is helpful if the economic savings of improved safety are highlighted, so that there is a clear overall economic gain showing that road safety is not just a social good, but a sound economic investment.

Community support – this should include all aspects of the community, particularly representatives from victim advocacy groups.

Transparency - to avoid criticism from opposition that views this type of enforcement as a “revenue generator”.

Demonstrate Leadership – Governments can be seen as true supporters of the importance of road safety, and specifically speed management. Road safety should be a non-political issue, therefore all parties should support the program to ensure that the program survives government elections.

Governments may also see risks in certain road safety policies, often based on poor or biased data (such as some claims about community views in the media). Appreciation of these government perceptions and opportunities to manage them can change political decision making. For example, media may present speed management as unpopular based on the vocal minority. In such cases, sound community surveys of attitudes and beliefs can show common support for better speed management.

You can find out how the French automated speed enforcement system was launched in November 2003 from a OECD study (Box 5.2), and also from the Global Alliance for NGOs for Road Safety resources on Political Commitment. The Commonwealth Road Safety Initiative (CRSI) and Governors Highway Safety Association (GHSA) also provide good examples. Information from international surveys on road user attitudes relating to speed can be found here.

Question Link:https://www.globalroadsafetyfacility.org/node/1089?ptab=5&pr=38&sr=968

Road safety is not only influenced by the average speed on a road, but also differences between the speed (also called speed variance) of the various modes of transport sharing the road. Roads with a large speed variance are considered less safe than roads with a small variance. This is not only valid for roads with motorized traffic but also for stretches of roads that slower pedestrians (such as the elderly or those with disabilities) must share with much faster cyclists or mobility scooters.

One of the added advantages of lower speed limits and managing speeds down is that this reduces differences in speeds between the inevitably slower users and others.

A large variability and big differences in the speeds of various road users in the same road space cause disturbances in the traffic flow and increase the risk of crash occurrence and severity. This might be the case, for example, if a straight and high-speed road section is followed by a narrower section with a lower speed, without adequate advance information for the road users. In such circumstances, consistency between road design and speed management is extremely important to provide road users with a predictable road environment encouraging safer driver behavior.

When it is not possible to segregate slow-speed traffic from high-speed road environment, lowering the speed of the facility may be the best option.

Question Link:https://www.globalroadsafetyfacility.org/node/1089?ptab=5&pr=38&sr=1002

Network and town planning practices need to reflect the needs of vulnerable road users and enable the adoption of Safe System speeds. Three of the more relevant examples are discussed here, namely: A) the Dutch functional network structure, B) the Spanish superblocks, and C) 20-minute neighborhoods.

Since the late 1990s, the Netherlands has incorporated sustainable safety into the categorization and layout of its road network and town planning – this is called, functional network structure. Based on two main functions of roads and streets, namely: flow and access, three road categories are distinguished in the Netherlands:

- Through roads allow traffic to travel from origin to destination as quickly and safely as possible ('flow'). Through roads may only be situated outside urban areas.

- Access roads offer direct access to residential areas at locations of origin and destination.

- Distributor roads connect the through roads with the access roads. Distributor roads are found in both urban and rural areas.

Most relevant to vulnerable road users, ‘access roads’, provide access to homes, businesses, schools, hospitals, shops, etc. Access roads can be mainly found in areas with a residential function. This means that all types of traffic mix here: pedestrians, cyclists, motorcycles, cars, and trucks.

In urban areas, access roads have a 30 kph speed limit. In addition to 30 kph access roads there are home-zones. Home-zones have a 15 kph speed limit and pedestrians can walk and play on the entire width of the street.

The adoption of functional network structure has had a large impact on road safety in the Netherlands. Read more about it here.

Superblocks are neighborhoods of several blocks (e.g. 9 blocks in Barcelona) where through traffic is, completely or partially, banned. They are accessible to local and access traffic, and community and emergency services. However, speed limits are lowered to between 10 and 30 kph.

A new town planning paradigm, superblocks are shown to prevent premature deaths, improve air quality, promote physical activity and prevent public health issues, e.g., road trauma.

Superblocks are also effective planning measures to manage speed and improve vulnerable road user safety. By dropping speed limits to levels that are compliant with the Safe System approach, Superblocks allow people of various ages and capabilities to adopt an active lifestyle. Compared to a default speed limit of 50 kph, a superblock with a speed limit of 20 kph can be almost 90% safer for pedestrians and cyclists.

More specifically, assessing a superblock through the Kinetic Energy Management Model (KEMM) lens, we see that superblocks fulfil three important traffic safety functions: a) they reduce people's exposure to cars, b) they create an environment that is easier to navigate and understand, and where the intrinsic risk of crashes is lower, and c) any potential collision is likely to occur at lower speeds and not be severely injurious to pedestrians and cyclists. Read more about superblocks here and here.

A successful planning approach, the 20-minute neighborhood emphasizes the value of living locally and providing people with active transport options to meet as many daily needs as possible within a 20-minute walk from home, with safe cycling and walking facilities and local transport options. Embedded in strategic urban planning of many cities, the 20-minute neighborhood is a promising tool to deliver healthy and environmentally friendly environments while ensuring safety and speed management measures as well. Specifically, it helps us manage exposure to traffic risk for some of the most vulnerable community groups such as children, persons with disabilities, women and the elderly, and creates justification to reduce speed and provide better walking/cycling facilities. Find Melbourne’s plan for its 20-minute neighborhoods here, the Paris example here (a 15-minute city) and information from Bogota here.

Question Link:https://www.globalroadsafetyfacility.org/node/1089?ptab=5&pr=38&sr=1007

The levels of Vulnerable Road Users (VRU) road trauma greatly increase when the posted speed is beyond the threshold advised by the Safe System approach – read more about these thresholds here and in Q1.4.

It is known that the human body is vulnerable and not ‘built’ to withstand impact forces greater than around 30 kph – any speed greater than this greatly increases the risk of dying or sustaining serious injuries. This risk is even greater for some of the VRU groups such as children, the elderly and people with disabilities. For an interesting exploration on how to ‘build’ a body to better withstand higher crash speeds, meet Graham here.

The relationship between VRU road trauma and posted speed limit is shown to be a positive correlation – in other words, when the speed limit is reduced, VRU road trauma is shown to decrease, and vice versa.

Considering that 30 kph is the Safe System compliant speed for pedestrian and cyclist safety, several jurisdictions have set widespread 30 kph zones across their dense urban areas. The City of Oslo (Norway), for example, achieved Zero pedestrian and cyclist fatalities by implementing a series of interventions. Since 2015, Oslo has implemented a series of traffic calming measures including around 500 speed humps and has lowered speed limits systematically so that almost two-thirds of the city’s network now has a speed limit of 30 kph. The city government is determined to make 30 kph the standard citywide speed limit in the future. Other cities around the world (for example Paris and cities in Spain) have now followed this 30 kph example.

It is also shown that if on a particular road the average speed increases, then the number of crashes will increase, with serious crashes increasing to a larger extent than less serious crashes. While this is a general rule, we can safely assume that this is the case for VRU road trauma as well. Read more about the relationship between speed and road trauma here.

The Road Safety Country Profiles guide points out that Safe speeds are a critical component of the Safe System approach offering powerful, inexpensive opportunities to save lives and debilitating injuries, especially for VRUs. However, the report points out that none of the Low-Income Countries (LICs) and only 3% of Middle-Income Countries (MICs) have adopted speed limits <= 30kph in their urban areas.

It should be noted that setting Safe System compliant speeds for VRUs safety purposes has significant safety benefits for vehicle occupant safety as well. As can be seen in Q1.4, speed limits less than or equal to 30 kph are well within the safety tolerance of vehicle occupants.

Question Link:https://www.globalroadsafetyfacility.org/node/1089?ptab=5&pr=38&sr=1008

The use of social marketing or publicity is an effective way to support enforcement operations and effectiveness. It is very important that road users are aware of the increased levels of enforcement activity through these communications strategies, and that they understand the reason behind it, otherwise behavioral changes are usually only short term.

Research has identified that the impacts of advertising and publicity alone have limited impact on changing driver behavior, and to be successful they do need to be accompanied by relevant and timely enforcement. Publicity as a stand-alone measure could increase community awareness of traffic safety issues, however, it has only a minimal effect on actual road user behavior and injury prevention.

The communication strategy should be focused on specific target groups (ages and demographics) and also related to specific locations and actions/objectives, such as inappropriate speeding occurrences, therefore aiming to reduce these incidents.

Objectives for public communications about speed management include:

-

Providing information to drivers and other road users about speed management actions and the change in behavior expected from them.

-

Motivating drivers to comply with speed limits and safe speeds.

-

Encouraging and motivating public support for actions addressing the speeding problem.

Print or broadcast media and other means of communications may be used to increase deterrence and voluntary compliance. Educating the driving public on the basis for speed limits and the community’s speed enforcement policy may also work to reduce speeds. While these types of media have been around for several years, more recently online social media campaigns appear to provide greater opportunities for the public to better engage and interact, not only exchanging/sharing information but also in changing the culture (social norms / social acceptance) around speeding. Social media is most important in reaching a younger audience. It is important (and valuable) to use social media as a way to engage people in the campaign, rather than as a one-way communications channel. For example, you can encourage followers and partners to share, re-tweet and like your campaign messages and visual content like photos, infographics, and film clips, and to promote the campaign to a wider audience. You can also invite people to give their views on the campaign topic and feedback on how the event went and post their own pictures and film clips. See also information in Q7.2 and Q7.5.

For detailed information on this topic, see the WHO ‘Road safety mass media campaigns toolkit’ here. Click here to learn about a GRSP award-winning speed campaign; another good example from BRAKE here; and a research study here.

Question Link:https://www.globalroadsafetyfacility.org/node/1089?ptab=5&pr=38&sr=1024

Road safety and speed management have long been recognized to be political issues. There are several cultural, social, and psychological factors that can lead to resistance to speed change. Often these are perceived barriers, but even this perception can reduce the appetite for changes in speed by decision makers. The most important action to counter this resistance would be to genuinely adopt a Safe System approach, increasing the focus of road safety resources on providing a system which forgives human error rather than imagining road users will ever be perfect.

Support must be actively sought – often over a longer period of time. In this context the following steps might be helpful:

-

Provide politicians in key ministries and their direct staff with state-of-the-art scientific facts and figures that speed and speeding are a major road safety (and public health) issues creating a significant economic burden;

-

Provide politicians with individual accounts of the impacts speed crashes had on the lives of their constituents;

-

Show that there are countermeasures that actually worked in other countries with similar contexts as their own countries (before-after-studies);

-

Present the possibility of pilot projects or tactical urbanism to try out countermeasures on a small scale or as a phased approach to instigating speed change;

-

When implementing countermeasures start with high-risk locations first (e.g., near schools, or at areas where many vulnerable road users are present) where the risk can be more easily be recognized by the community and decision makers, and the impacts will be greatest;

-

Conduct surveys to determine the public response to crash risk, speeding and the possible countermeasures;

-

Team up with senior government officials within key ministries and stakeholders who are in direct contact with the political level to support speed management activities;

-

Work with media representatives (including provision of training) to provide evidence-based information on the need for change, and the effectiveness of speed-related interventions;

-

Brief politicians in key ministries and their direct staff regularly on positive effects and successes of the speed management strategy.